I met the author of this piece, Danusha Goska, in Krakow last summer. A mutual acquaintance introduced us because of our love for and interest in Polish peasant and folk art. Since our time in Poland we have been developing a creative friendship. She is a brilliant writer and professor. She has written and published several books and keeps a powerful, insightful and informative blog about Polish stereotypes and Jewish/Polish relations and dynamics in particular. (Here is the link to this article as it appears on her blog: Bieganski the Blog: Falling Star - Poland Through One Work of Art:)

Her questioning and thought provoking insights spurred on by a piece of art printed on a postcard is a lesson in itself highlighting the mystery humankind deals with everyday, whether we acknowledge it or not. I now have a broader understanding of Eastern European / Polish thought, politics, aesthetic, psychology and history after reading this blog entry. So, I want to share this interesting piece with you. It is well worth the read.

Danusha has kindly given me permission to re-blog her piece on my blog. Thank you, Danusha! Feel free to visit her blog if topics like this and more interests you: http://bieganski-the-blog.blogspot.com/

Falling Star - Poland Through One Work of Art

Below is an early version of an essay that appears in the April 15, 2012 edition of the Journal of American Folklore, volume 125, issue 496. I thank editor James P. Leary for supporting my work. Irish-American Prof. Leary is a champion of scholarship on Polonia. I also thank JAF co-editor Thomas A. DuBois, and JAF editorial assistants Hilary Virtanen and Anne Rue.

As per JAF guidelines, I do not post the finished version of this essay here. I am posting an earlier version. Those wishing to cite this material are advised to access the JAF, available through your library.

In the mid-1990's, I took a folk art class with Henry Glassie. Glassie asked his students to select one work of art from a given culture and explain how that artwork offers an entrée into that culture. Glassie gave us free rein; we could select an item of folk, elite or popular art.

I chose to select an artwork from Poland. As a child of immigrants, I had grown up with Eastern European folk art. I'd traveled to Eastern Europe several times, to study, as a tourist, and to live with family. I had lived in Poland for the eventful year of 1988-89, while studying Polish language and culture at Krakow's Jagiellonian University. I would travel to Poland again, to attend a scholarly conference, during my time as a graduate student at IU.

When considering which work of art to use as an entrée into Polish culture, I confronted an embarrassment of riches. I could have chosen a Góral's, or highlander's, embroidered felt pants; a wycinanka or brilliant paper cutting from Łowicz; one of the szopki or miniature castles and cathedrals hand-crafted from metallic papers and displayed at Christmastime in Kraków. I could have chosen Jan Matejko's painting of Jan Sobieski after his 1683 victory against the Turks at Vienna, an event that Middle East scholar Bernard Lewis, post 9-11, identified as pivotal in Islam's relationship to the rest of the world. I could have chosen one of the films that won Andrzej Wajda an honorary Academy Award.

I could have attempted science, and chosen an item from Poland's geographic center, or from the Golden Age of folk art, by some estimates, the late nineteenth century, or one representing an art form common to Poland's varied populations, including peasants and nobility, Jews and Gypsies, and other regional or minority groups. I could have abandoned all hope of science, closed my eyes, spun the wheel, and pointed. There was the option to obey instinct, and to attempt to explain the powerful pull of the unarticulated.

During a yearlong visit in 1989, I was hiking through northern Poland. I stopped at Frombork, to pay respects to one of those Poles we Poles and Polish-Americans who engage in the unending struggle for dignity always cite: Copernicus. There I stepped into a small gallery. On the stone wall hung an artwork. I found myself staring at this artwork for a long time. Later, in the museum gift shop, I bought a postcard reproduction. The artwork was "Spadająca Gwiazda," "Falling Star," by Witold Masznicz. It was mixed media. An oil painting served as background; an unpainted, wooden, human figure occupied the foreground. From the few publications I have since found, I learned that Masznicz has displayed his works in various cities in Poland and the US, and that he has been influenced by medieval art. "Falling Star" was created in 1982, the year of Martial Law and the crushing of Solidarity. Another Polish artist, Witold Pruszkowski, also painted a "Spadająca Gwiazda" in 1884. Pruszkowski's oil painting has a dramatic, science-fiction look, very unlike Masznicz's. I don't know if Masznicz's artwork is a response to Pruszkowski's.

Since that hike in 1989, I've had twenty or thirty mailing addresses. I've long since given away as gifts all the paper cut-outs and carved wooden boxes I brought back with me from that trip to Poland. I have kept my flimsy little post-card reproduction of Masznicz's painting with me, though. Why? Searching in my mind for reasons for being so compelled by it, for keeping it for so long, I came to articulate why I had, intuitively, selected it as entrée into Polish art and culture.

The work is roughly rectangular, 23.5 by 20 by 9 centimeters, short sides top and bottom. The bottom is squared off, while the top rises to a curved arch, as in an altar triptych. The background is wood, painted midnight blue, with four white stars. A fiery yellow streak proceeds halfway down this sky. In the foreground lies an unpainted, human-like, wooden figure. This figure lies on a piece of wood which is lashed, by white cord, to the midnight blue background. The figure is lying in a fetal position, with its hands under its chin. Its joints are attached to each other, and also made mobile, by white cord. The grain of the wood is distinct; the grain runs vertically up and down the figure's legs, arms, and torso. The head is in the shape of an elongated sphere; here the wood's grain suggests, to the probing viewer, facial features. Perhaps one blotch is an eye, perhaps a streak is a nose? Nothing suggests a mouth. The figure lies directly under the fiery streak and looks to be its target.

This work is wordless, its principals gigantic and mythic. The human figure sports no clues as to sex, age, class, work, race, or even character. It assumes the ur human form: a fetal position. It has no mouth. The sky, too, is represented only in the broadest strokes that allow the viewer to know that this is a blue sky and not a blue table: the placement as background, four stars. A raised circular area in the paint's surface hints that the painter may have originally included some heavenly body, either moon or sun, but thought better of it. The chatter of facts that communicate individuality and individual experience has been expunged from this work, or this work represents a time when such chatter had not yet evolved. The viewer is confronted with the big, old nouns and verbs without definite articles: human / heaven / collision / destiny.

The viewer can be sure that collision is inevitable. It is plain from the trailing tail of the yellow blob that this is a falling star. It is aimed directly at the human form, right for the heart. This is not an artwork in which pleasure comes from being made to guess: "What's going to happen next?" The viewer is being informed of that, bluntly. Freed of plot uncertainty, the viewer turns to questions of value and meaning. "Why is this happening? Is it good or bad? Are the two visible agents: heaven and human, in compliance, or is one acting without the knowledge, or counter to the wishes, of the other?"

These questions are a matter of some urgency. When regarding this taciturn work, surveying it in a search for meaning, the viewer immediately recognizes the figure in front as like him or herself. It is human in the way that the viewer is human; it is not human in ways unlike the viewer. It is not of a different race or culture or age or profession. No distancing factors communicate that its fate belongs to a different set of experience than the viewer's fate. The viewer begins an urgent search for clues. One must find the clues before plunging heavenly star makes contact with targeted human heart.

Scanning the sky of this artwork, searching for meaning, is familiar to the viewer; scanning the sky for meaning is something humans have been doing for as long as we have been. The viewer sees what has been seen before: a beautiful shade of blue, the blue of night sky and the blue of deep ocean, a blue associated with meditative calm and profound mystery. No other features, no clouds, no horizon, no constellation, help out by providing further vocabulary or narrative. The viewer must make of this sky what he makes of any sky. Sky, of course, has been and can be the map for a sailor, the cosmic order for an astrologer or astronomer, the last frontier for a nation with an exhausted manifest destiny, the source of ultimate fear and destruction for the audiences of War of the Worlds and other films depicting attacks by space aliens. The viewer must make of this heaven what he makes of the heaven that is the metonym for fate, destiny, order, the heaven that is synecdoche for God. It is beautiful, informative, balanced, promising, terrifying, irrational, inexplicable, malicious, as the viewer holds in his own philosophy. Left only with mystery and his own forced conclusions based on insufficient data, the viewer turns to the human figure, hoping for more clues on which to develop or support a theory.

The figure is in a fetal pose. Is this the coil of new life ready to spring? A hologram for the helix? Is, then, the yellow streak sperm shooting from an ur father? Is this figure so blank, so apparently passive, so without feature, because it hasn't happened yet, and is waiting patiently and trustingly for heaven to come to earth in a generous, divine quickening? Or, horribly, is this the fetal position of sleep? Is this human not patient, but merely unaware? Has he surrendered to the promise of rest only to be annihilated for his indulgent and foolish relaxation of watchful tension? But then a creeping suspicion arises. Is this figure awake? Does he know what awaits him? Is his posture dictated not by the spatial economy of wombs or the reflexes of sleeping muscles, but, rather, by conscious decisions to lie down where one might stand, to crouch and be small where one might stretch and take up space, to curl silently where one might bounce violently, shake one's fist, yell and holler and shout? Is this just another one of those irritatingly bovine Poles, like those observed in bread lines, Kafkaesque bureaucratic offices, staring one in the face like human roadblocks when one is trying to get something done? Is this not the coil of hope or the innocence of sleep, but the product of long training, the manufactured posture of waking resignation?

Should we be as annoyed by this figure as we are by the plodding peasant in a slow cart taking up the whole, damn road? This one thing human in the beautiful, mute landscape represents humanity, us, and is no action hero, but rather is taking no action to save or to be saved. Or, do we feel a different anger? This figure is lying under a blissfully beautiful sky. A comet speeds across it, plain as day. For those of us who have stayed up late or driven far to see Haley, Kohoutek, Hale-Bopp, or some other ballyhooed celestial fireworks, this figure's apparent obliviousness is an affront. "Get some eyes!" we want to shout. "Open them and turn around and look! Behind you! An Event!"

I am fully aware of my own inner ungulate, of my own tendency to chew my cud, or, like the figure in "Falling Star," to revert to what looks like a duck-and-cover routine, a wake-me-when-it's-over strategy, when I might be fighting for rights, building a house of brick, or performing an aerobically therapeutic dance for joy. Should I blame my parents? They recounted, as living memory, the tale of the peasants who stood out (he worked too fast or too slow; she was too pretty or too smart; they sang a patriotic song within earshot of the wrong person) and, for their troubles, were tortured in the public square. Or is laying low as a survival strategy, not Slavic, but universal? I certainly encountered it among skittish American grad students, eager as serfs to identify and please the powers-that-be. A common folk metaphor among Polish Americans is "strong like bull" (from "silny jak tur.") The ability of peasants to be strong – or to be bovine – is beautifully dramatized in Andrzej Wajda's 1976 film "Man of Marble." The title is at least a double entendre. Despair at Poles' stoicism in the face of injustice, and awe at Poles' superhuman heroism in the face of catastrophe, are constants in Polish literature. William Butler Yeats is almost as Polish as he is Irish in his poem "Easter, 1916," when he speaks of the birth of a terrible beauty among Irishmen he'd previously dismissed as "drunken, vainglorious louts." My own aching awareness of stoicism's rewards, costs, and surprises invests me – with some urgency – in Witold Masznicz's artwork.

We study the figure's features for evidence to support one or the other of the above-proposed conclusions. The figure is lashed to the sky by cord. Similar, though finer, cord attaches limbs to torso. The same force that binds human figure to mythic sky holds human figure together. Can it be that the forces that keep us here on earth and elements in the mysterious plot are merely mechanical, and to be equated with muscles and tendons? Or, are muscles and tendons the equals of more mysterious, invisible forces? And are these forces benign or malicious?

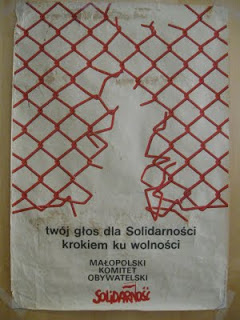

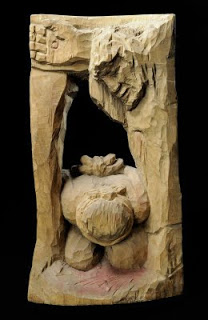

The figure looks bound. Figures restricted by ropes, vises, and walls were a common motif in Polish art during the communist era. This motif appeared on movie posters, street art, gallery art, and folk art. An example can be seen in Hans-Joachim Schauss's 1987 book Contemporary Polish Folk Artists. Józef Lurka, a Polish wood carver, produced a sickeningly claustrophobic figure of a kneeling human, hands bound behind back, blindfold over eyes, imprisoned between two oppressive blocks of wood. In Lurka's view, the captive's suffering has meaning; a Christ-like figure watches over him. The obvious interpretation of the oft-repeated motif of human forms restricted by ropes, blindfolds, fences, vises and walls, was that the obstacles represented Russia's communist hegemony, or that of Poland's previous oppressors and occupiers, for example, the Nazis. Support for this can be found on a Solidarity poster from 1989, which featured a red chain-link fence with a hole broken in it and the caption: "Your vote for Solidarity is a step toward freedom." No symbols inform the viewer that communism is the sole referent in "Falling Star," or even one referent among many. For example, given that Martial Law was declared by the Military Council for National Salvation, whose acronym spelled the root of the word "crow," crows were sometimes used to symbolize communist oppression. This symbol had further resonance; during the Nazi occupation, Poles referred to the German eagle as a "crow." It would be easy enough to put a crow in the sky of "Falling Star," but there is none.

The figure in "Falling Star" looks bound, and being bound suggests oppression and absence of free will. Too, given that the figure is carved of wood, these cords suggest puppetry. Is this figure a puppet of some divine puppet master? On closer inspection and further reflection, however, it becomes evident that the figure is not tied up, but merely tied. The strings do not proceed directly to heaven, or to anything outside the human figure. Rather, these strings, lashing joints, are the very elements that allow rigid wood the potential of movement, one of the requirements of, and evidence for, life. Yes, this figure could get up and run away, if it were awake, if it chose to. It could turn around and see. In any case, puppets in Eastern European folk tradition have not always been viewed as passive subjects of the manipulation of overwhelming force. In fact, puppets were potentially subversive enough that when Nazis arrested Czech puppet master Josef Skupa, they arrested his comic puppets, Spejbl and Hurvinek, also.

Perhaps this figure's posture provides clues. Take this rectangle, short ends top and bottom, and turn it on its right side. The figure is no longer fetal, rather, he is seated, with his head rested on his hands. Anyone familiar with Polish or neighboring Lithuanian folk art can tell you: this is the posture of the Worried Christ. "Chrystus Frasobliwy," variously translated as "Worried Christ," "Sorrowful Christ" or "Man of Sorrows," is the most frequently encountered male figure in Polish folk art. It can be found in roadside shrines and folk art shops, in several media such as wood, stone, or metal. Worried Christ shows Jesus at some point in his Passion, perhaps after being whipped. He is typically wearing a crown of thorns and a loincloth. He is seated, his head resting in his hands. He is weighed down by the weight of his suffering and his destiny, and yet the Worried Christ, his center of gravity low, is not without strength and dignity. This is a Christ who has been beaten, but who is not beaten. He wears his scars, even his humiliation, as a gravity that binds him closer to the powers of earth. He has been stripped of any distraction, any of the "unbearable lightness of being," as Czech novelist Milan Kundera put it in the title of his best-known work. No stray wind will blow him off course. His pose is meditative; it may be his own suffering that obsesses him, but, given the look of transcendent thought on his face, it may be experience itself. The seeker does not feel foolish coming to this semi-naked, whipped outcast to plead for intervention, does not feel selfish presenting personal woes to someone who so obviously has suffered himself.

The human form in "Falling Star" is not a Worried Christ. He wears no crown of thorns or loincloth; he is lying rather than seated. This form is, though, part of a tradition in which stoic inaction in the face of cataclysm has been represented as honorable, even mysteriously powerful. The tradition of the Worried Christ must be considered when assessing "Falling Star."

And so I look at it again. I have reported my speculations; I am "conclusion-free." This artwork rewards me at least partly because it contains enough data to inspire in me a bit of the sense of mystery I know when I ponder the night sky, or experience itself, and, like the night sky, like life, it provides me with no more data than that, certainly not enough to understand what anything means.

I selected this artwork as an entrée into Polish folk art and its wider culture not because it contains elements of folk art, although it does, for example, the arched, painted wood typical of an altar triptych, or a figure that may be compared to a puppet or to a Worried Christ, but because it symbolizes for me Polish artists, and the wider population there, and in all of Eastern Europe. Life anywhere is precarious and unpredictable; the precariousness of life seems underlined in Eastern Europe. Overwhelming and mysterious energies charge forward without let up: war upon war, the mass displacement of immigration, Nazism, communism, environmental catastrophe. The viewer questions: "Is this annihilation or spiritual opportunity?" No definitive statement has been formulated as yet. However, we have the art as testimony to what people can do, even with fire aimed at their hearts.

Her questioning and thought provoking insights spurred on by a piece of art printed on a postcard is a lesson in itself highlighting the mystery humankind deals with everyday, whether we acknowledge it or not. I now have a broader understanding of Eastern European / Polish thought, politics, aesthetic, psychology and history after reading this blog entry. So, I want to share this interesting piece with you. It is well worth the read.

Danusha has kindly given me permission to re-blog her piece on my blog. Thank you, Danusha! Feel free to visit her blog if topics like this and more interests you: http://bieganski-the-blog.blogspot.com/

Falling Star - Poland Through One Work of Art

|

| "Spadajaca Gwiazda" "Falling Star" by Witold Masznicz at the Nicolaus Copernicus Museum in Frombork. Source. |

|

"twoj glos dla Solidarnosci krokiem ku wolnosci."

"Your vote for Solidarity is a step toward freedom."

Poster from Krakow, Poland, 1989.

|

|

| Chrystus Frasobliwy or Worried Christ. Source. |

|

| Wood carving by Jozef Lurka. Source. |

Below is an early version of an essay that appears in the April 15, 2012 edition of the Journal of American Folklore, volume 125, issue 496. I thank editor James P. Leary for supporting my work. Irish-American Prof. Leary is a champion of scholarship on Polonia. I also thank JAF co-editor Thomas A. DuBois, and JAF editorial assistants Hilary Virtanen and Anne Rue.

As per JAF guidelines, I do not post the finished version of this essay here. I am posting an earlier version. Those wishing to cite this material are advised to access the JAF, available through your library.

On Witold

Masznicz's "Spadająca

Gwiazda" / "Falling Star"

In the mid-1990's, I took a folk art class with Henry Glassie. Glassie asked his students to select one work of art from a given culture and explain how that artwork offers an entrée into that culture. Glassie gave us free rein; we could select an item of folk, elite or popular art.

I chose to select an artwork from Poland. As a child of immigrants, I had grown up with Eastern European folk art. I'd traveled to Eastern Europe several times, to study, as a tourist, and to live with family. I had lived in Poland for the eventful year of 1988-89, while studying Polish language and culture at Krakow's Jagiellonian University. I would travel to Poland again, to attend a scholarly conference, during my time as a graduate student at IU.

When considering which work of art to use as an entrée into Polish culture, I confronted an embarrassment of riches. I could have chosen a Góral's, or highlander's, embroidered felt pants; a wycinanka or brilliant paper cutting from Łowicz; one of the szopki or miniature castles and cathedrals hand-crafted from metallic papers and displayed at Christmastime in Kraków. I could have chosen Jan Matejko's painting of Jan Sobieski after his 1683 victory against the Turks at Vienna, an event that Middle East scholar Bernard Lewis, post 9-11, identified as pivotal in Islam's relationship to the rest of the world. I could have chosen one of the films that won Andrzej Wajda an honorary Academy Award.

I could have attempted science, and chosen an item from Poland's geographic center, or from the Golden Age of folk art, by some estimates, the late nineteenth century, or one representing an art form common to Poland's varied populations, including peasants and nobility, Jews and Gypsies, and other regional or minority groups. I could have abandoned all hope of science, closed my eyes, spun the wheel, and pointed. There was the option to obey instinct, and to attempt to explain the powerful pull of the unarticulated.

During a yearlong visit in 1989, I was hiking through northern Poland. I stopped at Frombork, to pay respects to one of those Poles we Poles and Polish-Americans who engage in the unending struggle for dignity always cite: Copernicus. There I stepped into a small gallery. On the stone wall hung an artwork. I found myself staring at this artwork for a long time. Later, in the museum gift shop, I bought a postcard reproduction. The artwork was "Spadająca Gwiazda," "Falling Star," by Witold Masznicz. It was mixed media. An oil painting served as background; an unpainted, wooden, human figure occupied the foreground. From the few publications I have since found, I learned that Masznicz has displayed his works in various cities in Poland and the US, and that he has been influenced by medieval art. "Falling Star" was created in 1982, the year of Martial Law and the crushing of Solidarity. Another Polish artist, Witold Pruszkowski, also painted a "Spadająca Gwiazda" in 1884. Pruszkowski's oil painting has a dramatic, science-fiction look, very unlike Masznicz's. I don't know if Masznicz's artwork is a response to Pruszkowski's.

Since that hike in 1989, I've had twenty or thirty mailing addresses. I've long since given away as gifts all the paper cut-outs and carved wooden boxes I brought back with me from that trip to Poland. I have kept my flimsy little post-card reproduction of Masznicz's painting with me, though. Why? Searching in my mind for reasons for being so compelled by it, for keeping it for so long, I came to articulate why I had, intuitively, selected it as entrée into Polish art and culture.

The work is roughly rectangular, 23.5 by 20 by 9 centimeters, short sides top and bottom. The bottom is squared off, while the top rises to a curved arch, as in an altar triptych. The background is wood, painted midnight blue, with four white stars. A fiery yellow streak proceeds halfway down this sky. In the foreground lies an unpainted, human-like, wooden figure. This figure lies on a piece of wood which is lashed, by white cord, to the midnight blue background. The figure is lying in a fetal position, with its hands under its chin. Its joints are attached to each other, and also made mobile, by white cord. The grain of the wood is distinct; the grain runs vertically up and down the figure's legs, arms, and torso. The head is in the shape of an elongated sphere; here the wood's grain suggests, to the probing viewer, facial features. Perhaps one blotch is an eye, perhaps a streak is a nose? Nothing suggests a mouth. The figure lies directly under the fiery streak and looks to be its target.

This work is wordless, its principals gigantic and mythic. The human figure sports no clues as to sex, age, class, work, race, or even character. It assumes the ur human form: a fetal position. It has no mouth. The sky, too, is represented only in the broadest strokes that allow the viewer to know that this is a blue sky and not a blue table: the placement as background, four stars. A raised circular area in the paint's surface hints that the painter may have originally included some heavenly body, either moon or sun, but thought better of it. The chatter of facts that communicate individuality and individual experience has been expunged from this work, or this work represents a time when such chatter had not yet evolved. The viewer is confronted with the big, old nouns and verbs without definite articles: human / heaven / collision / destiny.

The viewer can be sure that collision is inevitable. It is plain from the trailing tail of the yellow blob that this is a falling star. It is aimed directly at the human form, right for the heart. This is not an artwork in which pleasure comes from being made to guess: "What's going to happen next?" The viewer is being informed of that, bluntly. Freed of plot uncertainty, the viewer turns to questions of value and meaning. "Why is this happening? Is it good or bad? Are the two visible agents: heaven and human, in compliance, or is one acting without the knowledge, or counter to the wishes, of the other?"

These questions are a matter of some urgency. When regarding this taciturn work, surveying it in a search for meaning, the viewer immediately recognizes the figure in front as like him or herself. It is human in the way that the viewer is human; it is not human in ways unlike the viewer. It is not of a different race or culture or age or profession. No distancing factors communicate that its fate belongs to a different set of experience than the viewer's fate. The viewer begins an urgent search for clues. One must find the clues before plunging heavenly star makes contact with targeted human heart.

Scanning the sky of this artwork, searching for meaning, is familiar to the viewer; scanning the sky for meaning is something humans have been doing for as long as we have been. The viewer sees what has been seen before: a beautiful shade of blue, the blue of night sky and the blue of deep ocean, a blue associated with meditative calm and profound mystery. No other features, no clouds, no horizon, no constellation, help out by providing further vocabulary or narrative. The viewer must make of this sky what he makes of any sky. Sky, of course, has been and can be the map for a sailor, the cosmic order for an astrologer or astronomer, the last frontier for a nation with an exhausted manifest destiny, the source of ultimate fear and destruction for the audiences of War of the Worlds and other films depicting attacks by space aliens. The viewer must make of this heaven what he makes of the heaven that is the metonym for fate, destiny, order, the heaven that is synecdoche for God. It is beautiful, informative, balanced, promising, terrifying, irrational, inexplicable, malicious, as the viewer holds in his own philosophy. Left only with mystery and his own forced conclusions based on insufficient data, the viewer turns to the human figure, hoping for more clues on which to develop or support a theory.

The figure is in a fetal pose. Is this the coil of new life ready to spring? A hologram for the helix? Is, then, the yellow streak sperm shooting from an ur father? Is this figure so blank, so apparently passive, so without feature, because it hasn't happened yet, and is waiting patiently and trustingly for heaven to come to earth in a generous, divine quickening? Or, horribly, is this the fetal position of sleep? Is this human not patient, but merely unaware? Has he surrendered to the promise of rest only to be annihilated for his indulgent and foolish relaxation of watchful tension? But then a creeping suspicion arises. Is this figure awake? Does he know what awaits him? Is his posture dictated not by the spatial economy of wombs or the reflexes of sleeping muscles, but, rather, by conscious decisions to lie down where one might stand, to crouch and be small where one might stretch and take up space, to curl silently where one might bounce violently, shake one's fist, yell and holler and shout? Is this just another one of those irritatingly bovine Poles, like those observed in bread lines, Kafkaesque bureaucratic offices, staring one in the face like human roadblocks when one is trying to get something done? Is this not the coil of hope or the innocence of sleep, but the product of long training, the manufactured posture of waking resignation?

Should we be as annoyed by this figure as we are by the plodding peasant in a slow cart taking up the whole, damn road? This one thing human in the beautiful, mute landscape represents humanity, us, and is no action hero, but rather is taking no action to save or to be saved. Or, do we feel a different anger? This figure is lying under a blissfully beautiful sky. A comet speeds across it, plain as day. For those of us who have stayed up late or driven far to see Haley, Kohoutek, Hale-Bopp, or some other ballyhooed celestial fireworks, this figure's apparent obliviousness is an affront. "Get some eyes!" we want to shout. "Open them and turn around and look! Behind you! An Event!"

I am fully aware of my own inner ungulate, of my own tendency to chew my cud, or, like the figure in "Falling Star," to revert to what looks like a duck-and-cover routine, a wake-me-when-it's-over strategy, when I might be fighting for rights, building a house of brick, or performing an aerobically therapeutic dance for joy. Should I blame my parents? They recounted, as living memory, the tale of the peasants who stood out (he worked too fast or too slow; she was too pretty or too smart; they sang a patriotic song within earshot of the wrong person) and, for their troubles, were tortured in the public square. Or is laying low as a survival strategy, not Slavic, but universal? I certainly encountered it among skittish American grad students, eager as serfs to identify and please the powers-that-be. A common folk metaphor among Polish Americans is "strong like bull" (from "silny jak tur.") The ability of peasants to be strong – or to be bovine – is beautifully dramatized in Andrzej Wajda's 1976 film "Man of Marble." The title is at least a double entendre. Despair at Poles' stoicism in the face of injustice, and awe at Poles' superhuman heroism in the face of catastrophe, are constants in Polish literature. William Butler Yeats is almost as Polish as he is Irish in his poem "Easter, 1916," when he speaks of the birth of a terrible beauty among Irishmen he'd previously dismissed as "drunken, vainglorious louts." My own aching awareness of stoicism's rewards, costs, and surprises invests me – with some urgency – in Witold Masznicz's artwork.

We study the figure's features for evidence to support one or the other of the above-proposed conclusions. The figure is lashed to the sky by cord. Similar, though finer, cord attaches limbs to torso. The same force that binds human figure to mythic sky holds human figure together. Can it be that the forces that keep us here on earth and elements in the mysterious plot are merely mechanical, and to be equated with muscles and tendons? Or, are muscles and tendons the equals of more mysterious, invisible forces? And are these forces benign or malicious?

The figure looks bound. Figures restricted by ropes, vises, and walls were a common motif in Polish art during the communist era. This motif appeared on movie posters, street art, gallery art, and folk art. An example can be seen in Hans-Joachim Schauss's 1987 book Contemporary Polish Folk Artists. Józef Lurka, a Polish wood carver, produced a sickeningly claustrophobic figure of a kneeling human, hands bound behind back, blindfold over eyes, imprisoned between two oppressive blocks of wood. In Lurka's view, the captive's suffering has meaning; a Christ-like figure watches over him. The obvious interpretation of the oft-repeated motif of human forms restricted by ropes, blindfolds, fences, vises and walls, was that the obstacles represented Russia's communist hegemony, or that of Poland's previous oppressors and occupiers, for example, the Nazis. Support for this can be found on a Solidarity poster from 1989, which featured a red chain-link fence with a hole broken in it and the caption: "Your vote for Solidarity is a step toward freedom." No symbols inform the viewer that communism is the sole referent in "Falling Star," or even one referent among many. For example, given that Martial Law was declared by the Military Council for National Salvation, whose acronym spelled the root of the word "crow," crows were sometimes used to symbolize communist oppression. This symbol had further resonance; during the Nazi occupation, Poles referred to the German eagle as a "crow." It would be easy enough to put a crow in the sky of "Falling Star," but there is none.

The figure in "Falling Star" looks bound, and being bound suggests oppression and absence of free will. Too, given that the figure is carved of wood, these cords suggest puppetry. Is this figure a puppet of some divine puppet master? On closer inspection and further reflection, however, it becomes evident that the figure is not tied up, but merely tied. The strings do not proceed directly to heaven, or to anything outside the human figure. Rather, these strings, lashing joints, are the very elements that allow rigid wood the potential of movement, one of the requirements of, and evidence for, life. Yes, this figure could get up and run away, if it were awake, if it chose to. It could turn around and see. In any case, puppets in Eastern European folk tradition have not always been viewed as passive subjects of the manipulation of overwhelming force. In fact, puppets were potentially subversive enough that when Nazis arrested Czech puppet master Josef Skupa, they arrested his comic puppets, Spejbl and Hurvinek, also.

Perhaps this figure's posture provides clues. Take this rectangle, short ends top and bottom, and turn it on its right side. The figure is no longer fetal, rather, he is seated, with his head rested on his hands. Anyone familiar with Polish or neighboring Lithuanian folk art can tell you: this is the posture of the Worried Christ. "Chrystus Frasobliwy," variously translated as "Worried Christ," "Sorrowful Christ" or "Man of Sorrows," is the most frequently encountered male figure in Polish folk art. It can be found in roadside shrines and folk art shops, in several media such as wood, stone, or metal. Worried Christ shows Jesus at some point in his Passion, perhaps after being whipped. He is typically wearing a crown of thorns and a loincloth. He is seated, his head resting in his hands. He is weighed down by the weight of his suffering and his destiny, and yet the Worried Christ, his center of gravity low, is not without strength and dignity. This is a Christ who has been beaten, but who is not beaten. He wears his scars, even his humiliation, as a gravity that binds him closer to the powers of earth. He has been stripped of any distraction, any of the "unbearable lightness of being," as Czech novelist Milan Kundera put it in the title of his best-known work. No stray wind will blow him off course. His pose is meditative; it may be his own suffering that obsesses him, but, given the look of transcendent thought on his face, it may be experience itself. The seeker does not feel foolish coming to this semi-naked, whipped outcast to plead for intervention, does not feel selfish presenting personal woes to someone who so obviously has suffered himself.

The human form in "Falling Star" is not a Worried Christ. He wears no crown of thorns or loincloth; he is lying rather than seated. This form is, though, part of a tradition in which stoic inaction in the face of cataclysm has been represented as honorable, even mysteriously powerful. The tradition of the Worried Christ must be considered when assessing "Falling Star."

And so I look at it again. I have reported my speculations; I am "conclusion-free." This artwork rewards me at least partly because it contains enough data to inspire in me a bit of the sense of mystery I know when I ponder the night sky, or experience itself, and, like the night sky, like life, it provides me with no more data than that, certainly not enough to understand what anything means.

I selected this artwork as an entrée into Polish folk art and its wider culture not because it contains elements of folk art, although it does, for example, the arched, painted wood typical of an altar triptych, or a figure that may be compared to a puppet or to a Worried Christ, but because it symbolizes for me Polish artists, and the wider population there, and in all of Eastern Europe. Life anywhere is precarious and unpredictable; the precariousness of life seems underlined in Eastern Europe. Overwhelming and mysterious energies charge forward without let up: war upon war, the mass displacement of immigration, Nazism, communism, environmental catastrophe. The viewer questions: "Is this annihilation or spiritual opportunity?" No definitive statement has been formulated as yet. However, we have the art as testimony to what people can do, even with fire aimed at their hearts.